Racine

God, give us the serenity to accept what cannot be changed; Give us the courage to change what should be changed; Give us the wisdom to distinguish one from the other.

- Reinhold Niebuhr 1892-1971

1983 – 1990

Back to Industry

SC Johnson Wax (SCJW) made me an offer I couldn’t refuse: Vice President for Corporate Research with a substantial increase in pay. But more importantly for me it meant that I could have a substantial role in forming a world-class R & D organization, with strong emphasis on polymer and colloid chemistry. In this I knew that I had full and enthusiastic support from my new boss, Donald Buyske, Senior Vice President for Research and Development World-Wide and Chief Scientific Officer – quite a title! Just a few years earlier the company had undertaken a thoroughgoing restructuring that resulted in the lofty position that Buyske now held. It meant that R & D had a seat at the senior management table, recognition of its importance to the future innovative prowess of the corporation and a means of greasing the skids to facilitate the launching of new technologies. Don was an excellent choice, coming as he did from the drug industry, renowned for its emphasis on a combination of basic and applied research.

As an external consultant I had noticed over the previous year a pronounced improvement in morale among the scientists with whom I met, a sense that they were looked upon as real professionals. Their self-esteem had been elevated. Buyske’s influence was visible. There was still much to be done, but the climate was now favorable for change.

Corporate Research

The Corporate Research Division was comprised of a group providing services, such as chemical and physical analyses, to all divisions of the company. In addition they were responsible for developing new technologies upon which new product lines could be based. Sam Johnson, the Chairman of this privately held company, told me how happy he was that I had joined. He said that he wanted a technology-based company, and cited 3M as a model. I stated to him and to Ray Farley, the CEO, that it would take about ten years for that to happen, and I asked if he could stay the course for that long. I didn’t get an enthusiastic “Absolutely!” or “Go for it!” but rather a quiet grinding of the gears in their minds as they contemplated the proposition. At the time I was satisfied with their tacit acceptance. I should have got it in writing.

Building new strengths

So I set about to transform the organization by introducing:

Basic research by those people who had the ability and inclination. Their results were to be published in external, peer-reviewed scientific journals.

Cooperative research with other, external organizations to leverage our skills in areas where our expertise was limited.

Strategic planning to ensure that we were focused in our work and aligned with the overall thrust of the company.

Recognition of excellent work through awards and creation of a scientific promotions ladder.

Seminars by outside scientists to enhance our awareness of developments in the rest of the world, and

Development of library resources and an internal reports archive, among others.

Prior to Don Buyske’s arrival there were almost no incentives in all of R & D for those people to seek life-long improvement in their skills as scientists. If they were pursuing advanced degrees in addition to working, it was the Master’s of Business Administration, the MBA. Publication of research results would certainly enhance self-esteem, but it would also accomplish much more. The wider scientific world would regard us as a strong organization with which they might wish to work, and recruiting of new talent would not only be easier, but also allow us to reach the best graduate schools. Furthermore, with strategic selection of research programs we would lay the groundwork for developing new technologies which could be patented and from which whole new product lines could be derived if we were successful.

A single example can illustrate: several years after I arrived a young physicist, whom I had hired into our Physical Research Group, developed a theory for optimal performance of furniture polish films on, say, a wood surface. It involved light scattering, specular reflectance, color, and multiple layers of polish materials with a prescribed variation in their refractive indexes. On the basis of that a polymer scientist synthesized a family of prototype silicone block copolymers that we hoped would exhibit these properties. .

Working with other companies

We had approached the Dow-Corning company about this because they were a premier organization in silicone polymer research and development. We asked them to develop copolymers with these specifications, but after a couple of years of trying they failed. One of our chemists, whom I also had hired, in the meantime had succeeded in synthesizing some candidate polymers, as mentioned above. What was really exciting was that these new materials held promise for many applications from polishes to skin lotions, to marine anti-barnacle coatings, to specialized emulsifiers and others. And we had beaten Dow-Corning at their own game!

Another example was a cooperative project with another Corning Glass subsidiary, Genencor, which they had organized with Genentech, the premier biotech company at the time. We wanted to develop a product to dissolve hair, and decided that we needed an enzyme concoction to do it. Genencor was very strong in enzyme technology. It was exciting to be working with a first-rate company with a very strong research organization. They took us seriously, and we worked well together for about two years. Finally we were unable to meet the performance criteria we had jointly established, so that the project was ultimately terminated. But it proved that our scientists were as good as those in other world-class companies, and that we could work with them.

Strategic planning

The company had a strategic plan, but it was rather superficial, and I couldn’t see that anyone paid it attention once it was drafted. Most work seemed to be guided by the exigencies of the moment. I felt we in R & D needed something much more definitive, that we could take seriously, that would be formulated in cooperation with our ‘clients’ within the company, so that they would have an opportunity to ‘buy-in’ to our work and be supportive of it. For me this was always a difficult process. I don’t know why, but I was totally dedicated to the principal of strategic planning, and I kept struggling along with the managers reporting to me to get it right. Initially it was primarily a matter of prioritizing projects, attempting to strike a good balance between basic and applied work, and ensuring that we stayed within budget. The amount of money we had to spend I negotiated with Buyske, and he tended to be generous. Over time we learned how to develop strong strategic plans.

With regard to internal publications, there seemed to be almost none. That meant that we could be condemned endlessly to repeat past work because there was no record of it. So I required research reports to be written on a regular basis, and for these to be deposited and catalogued in the R & D Library. We would start to build the R & D archives. We also put up a bulletin board in the library to show off publications by our scientists in external journals. It served not only as a source of pride for the authors, but also as a stimulus for others. To further our sense of pride, a sense of community, and to communicate overall divisional goals and accomplishments, I started a newsletter that later was expanded to include all of R & D, not just Corporate Research.

Our most important resource: People

The biggest opportunity I had was in building a first rate team, particularly in polymer science, through the hiring of new people and the acquisition of state-of-the-art equipment. A few of my former students joined the group, and proved themselves to be excellent researchers. I hired Dr. John Pochan, who had been with Xerox and Eastman Kodak Research, and who was highly regarded in the field. He was put in charge of Polymer Research, and in turn hired some great talent. It didn’t take long before SC Johnson Wax was looked upon as having one of the best corporate polymer R & D groups in the world.

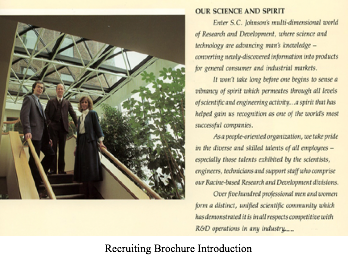

To enhance our image among prospective scientists I decided that we needed a recruiting brochure, something that would proudly display our scientific and technological strengths, our physical facilities, and the challenges that make a career at SC Johnson inviting. The result was an attractive booklet entitled Our Future is Now. It had lots of pictures of scientists at work at their highly advanced instruments, and in seminars, etc., and it spoke to all aspects of our research and development.

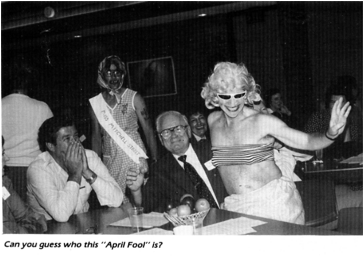

We then initiated the Technical Merit Awards to recognize scientific achievement. More of this later. I also wanted to create a more informal atmosphere and a sense that we were all in this together. So I organized a big potluck dinner with all staff and their spouses/ partners, and asked my managers to do

something a bit special for after-dinner entertainment. I asked them – all men – to dress as women and come out as a kick-line with some bump-and-grind music and just goof off for the fun of it. It took some coaxing, but they all finally agreed, and it was a huge success. The crowd roared with laughter. I don’t believe they had ever seen their management acting that way for the sheer fun of it, and letting down barriers. Gosh, they could relate to us as human beings! I have to admit that the “April Fool” in this picture is yours truly, with a couple of tennis balls tucked in for enhancement of curves. One of the other managers with the “Miss Mitchell Street” banner is in the background.

I had been at Johnson Wax just two years when my boss left rather precipitously. I believe he was fired. He did not like the policies of the CEO, and was not shy about expressing his opinions. As a result I suppose his departure was inevitable. A short time later (I mean hours) I was summoned by Sam Johnson and Ray Farley, the President, and was offered the job of Senior Vice President and Chief Scientific Officer Worldwide (CSO), and could they have my decision by 8:00 the next morning! Well, I really didn’t want the job, although the challenge was great and I would have the power to make major changes, or so I thought. But I knew it meant no longer being involved so much with science, and much more with management. I would have overall responsibility for about 800 people in labs in Racine, London, Japan, the Philippines and elsewhere. But when I considered who might be my new boss if I declined the offer, I decided I should take it. Suddenly I was catapulted into the highest ranks of corporate life, one of about 10 people sitting around the table of the Office of the Chairman in the ‘penthouse’ of the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed administration building. It was pretty heady stuff!

First Days as Sr. V.P.

There was a fairly big management meeting in Racine the day that I was promoted, and thus the announcement could be made of my new position to the attendees. Because of the shortness of time involved, I had a conflict with a scientific conference that started the following day in Santa Barbara, California. I didn’t see how I could withdraw from that obligation; so it was arranged that I would take the company plane to California after the senior management meeting. The latter was concluded by a very nice banquet at which my new position was announced, and then just as I finished a lovely strawberry mousse, I heard the whir of a helicopter outside the building. It took me to the Chicago airport where the two pilots of the company jet were waiting for me, and off we went. Just a few hours later the sound of waves lapping on the balmy beach of Santa Barbara were welcoming me. I could get used to this!

On my return it was quickly down to business, firstly learning a host of new things, including the R & D labs overseas, engineering, design and the research and technology being developed in each of the marketing divisions of the company, e.g. consumer products, commercial products, polymer products etc. There were so many things I didn’t know, and had to learn. As a professor I had run my research group somewhat like a benevolent despot. In a commercial/industrial organization I soon learned that such a management philosophy just didn’t work. Fortunately I had senior managers who were helpful in bringing me into this new environment. The company provided professional management consultants as well. Initially I was almost insulted to think that I could not run this organization with my current set of skills. But I soon came to appreciate how much I needed to learn.

My enthusiasm was somewhat tempered when I saw for the first time the display of SCJ products just outside a conference room. The items were certainly useful for the citizens of the world in helping to give a little shine and sparkle to our everyday lives, but the packaging was so pedestrian that it made my heart sink. In my new position, though, our package design team now reported to me, and I encouraged them whenever possible to be more creative and to put modern pizzazz into the appearance of our products. They responded better than I could have hoped.

Motivating and Enabling Scientists

We needed to provide our scientists with goals to which they could aspire, and to provide recognition when they achieved them, or had shown extraordinary performance along the way. The former were provided with a strategic plan, and for the latter we established three levels of recognition:

R& D Awards

Technical Merit Awards

Directors’ Award

that would be presented annually with appropriate fanfare and publication. We established a gallery in one of the hallways of our building with portraits of all the winners.

The scientists seemed to work in their own arenas with little knowledge of what other divisions of the company were up to. For instance, a group in England could be in the early stages of developing a novel air freshener technology that, unbeknownst to them, was something ready to go to market from Racine. We needed a mechanism whereby scientists in our labs around the world could more effectively know what others in the company were doing. So I brought a few of our people together and asked them to do something about it. The result was ITEX, the Information and Technology Exchange event. This was immediately popular and well attended, and greatly appreciated.

Further towards keeping us all in touch, the Corporate R&D News was greatly expanded to an overall R&D News. And I had a special column in each: ‘Letter from the CSO” to try and explain why I was undertaking various innovations and what my operating philosophy was.

New Ventures & Licensing

I also realized that in our efforts to encourage innovation and entrepreneurship, we needed an institutional structure to take advantage of any inventions that arose. So I added to Emer’s duties a ‘New Ventures’ function. With his growing contacts with the outside world of technologies, he might discover a potential user of a new technology that Johnson might not want, but that could generate a nice revenue stream through licensing.

All of this required acts of faith on the part of various other divisions of the company. It was all very forward-looking, since there would not be any income for several years, and adequate funding would be required in the interim. This would be regarded by other corporate divisions with jealousy. But at least one great advantage of a privately held company is that such ventures can more easily be sustained.

BASF & DuPont

I had worked for DuPont and had consulted for BASF, two of the largest chemical companies in the world. Thus I knew we had overlapping technologies. So I thought we might have joint opportunities for cross-licensing and perhaps even some cooperative research and development. My main focus was on a manufacturing process that our engineers had developed to rapidly and cheaply produce water-soluble polymers of low molecular weight. They would be useful in adhesives, floor finishes, printing inks and related applications. So I took a team of our guys to Wilmington, Delaware, home of DuPont, to drum up some interest. I knew that they had just developed an extremely sophisticated, revolutionary (and expensive) process for making similar polymers, but with very narrow molecular size distribution. Our polymers were narrow in size distribution, but not as much so. So they looked down their noses at ours, even though we could make them for a much lower cost, and they would function just as well in almost all conceivable applications. But the DuPont folks were just too proud, so that we went home without a deal.

Then we took the company plane to Ludwigshafen, Germany, the home of BASF. They looked at our process, and said that they had invented it and that they had all the basic patents on it, and that we could license from them. In due course, back home, we got a fairly large package in the mail – about eight inches thick – of all of their patents. I figured, well I guess that’s that. But the head of our patents group said he felt, after looking at them carefully, that they didn’t really cover our invention, and that we should proceed with patent applications – both in the US and even in Europe, BASF’s home turf! In due course, we succeeded in obtaining coverage. No doubt the guys at BASF must have been livid. They certainly tried as hard as they could to defeat our efforts. One result was, I learned, that I was banned from ever visiting them again. Too bad and pretty silly, because I had real friends there.

Quality Control

It turned out that one of the responsibilities of Chief Scientific Officer was quality control in manufacturing of all products. As a result I received regular reports from the production lines that showed how many rejections occurred for products that didn’t conform to quality standards. The process involved, for example, an examination of every aerosol can as it came off the production for any flaws.

It turned out that something like three percent of all cans of GladeⓇ ‘air freshener’ were rejected out of an annual production of millions. This was a huge number, and I could hardly believe that this was regarded as somehow acceptable. I brought this to the attention of our CEO, who agreed it was pretty large, but seemed relatively relaxed about what could be done about it.

So I got busy, and soon found the work of J. Edwards Deming, a professor at New York University and founder of his own consulting company. Deming had almost single handedly brought Japan after the second world war from making poor quality, tinny toys from US scrap metal to an industrial giant known for the high quality of its products. As a single example, Japan was able to make huge inroads into the global automobile markets once totally dominated by the United States. I was told that Deming previously had approached the likes of General Motors, Ford and Chrysler and was rejected.

The basic Deming idea was simply that one has to build quality into every aspect of production, not inspect and reject at the end of the line. But he further emphasized that the transformation had to be embraced by every component of a corporation, not just manufacturing. So every person on the production line was given the skills to plot the distribution of measurements of the items for which he was responsible and plot the data to produce what would always be a statistical distribution. And then he was to produce proposals on how to narrow that distribution so that his part would be more precisely made and thus more reliable and better performing over time.

Management in the meantime would be trained in the overall system as well, so that the entire company became obsessed with building in quality to all of its products. Deming showed that this could be done with lowered costs of production as well as higher quality of products, leading of course to higher profits and greater competitiveness. No wonder that Toyota, Honda, Mitsubishi and Mazda so successfully entered the global car and truck markets, and took so much of it away from the US automakers.

I brought in my Vice President for R&D Engineering who thereupon researched the field and started the long process of getting himself and his staff informed and on board. I also discussed this new way of quality assurance with my colleague Bob McCurdy, Sr. V.P. for Manufacturing. Jointly we identified a consultant who had successfully brought the Deming procedures to other companies, with whom we started the process of training people in all the relevant divisions of the company, initially with senior management, from Sam Johnson on down. Ultimately this was a complete transformation of the entire company.

My Office

With my new, (ahem!) prestigious position I moved into the former office of Don Buyske, my predecessor. It was furnished with conventional corporate desks and chairs. It was in the relatively new R&D building that earlier had been a hospital. I had been given a modest budget to renovate the room more to my liking. The large windows looked out upon the adjacent Frank Lloyd Wright buildings, and I thought that my office should reflect the same spirit of inspired design, whilst not copying Wright’s ideas.

Our son Doug was in Racine at the time, and pleaded with me to allow him to do the renovation. He had majored in art and design at Harvard, earning a “Summa cum Laude” degree, and had some experience in designing homes and houses, so that I decided to let him at it. Besides, he was cheap!

Doug started with building life-size cardboard mockups of my desk, cabinets and chairs in our garage, and each night he would set me down and ask what my needs were and how things fit. Because of the limited area and the fact that at times when I had visitors for informal meetings, I wanted a coffee table, whereas at other times we would need a working table for papers, documents, etc. for formal meetings, we came up with the idea of a convertible table: the top could move (by hydraulic lift) from a lower – coffee – to an upper – conference – position.

Doug had designed a carpet of many colors and had had it made in China, a very modern design hand-crafted in ancient Chinese wool tradition. It ended up on the wall of my office.

As they say, ‘you can take the professor out of the university, but you can’t take the university out of the professor.’ So I needed a blackboard, and that covered a major part of another wall (not shown). I also still gave occasional lectures and needed a place to store and view my slides (this, before Power Point). So in a niche behind my desk a drawer was designed to hold 35 mm slides, and above it there was a light table for viewing them, that when pulled out like a drawer, the light would come on.

My desk was totally functional, with ‘in-out’ trays, a reading rack that slid out of its own ‘dock’, shelves for active documents, file cabinets and bookshelves immediately within reach and a corner drawer. The cutoff corner on my right was actually the front of a small drawer. It was the cabinetmaker’s nightmare/triumph to make it so beautifully and functional in such difficult geometry. … and all just to hold a couple of pens and pencils. Kudos to Architectural Woodwork Co. of Racine who were allowed to take their time to be sure and do it right!

The overall result, when translated from wood and plastic and textiles and lights, was the most beautiful and functional working environment that I have ever experienced. The pictures here give a small idea of the space.

Security

My office overlooked the lobby of our beautiful R & D building. I began to notice the comings and goings of people, in particular those who were not part of our organization, e.g. sales representatives, focus groups, workmen, and technical consultants. There was a receptionist who would help in making appropriate contacts when requested, but she made no real effort to challenge anyone’s need to enter.

A Matter of Dress

In academia people in the sciences generally dressed for protection from the elements: a comfortable sweater on cool days, a casual pair of slacks, and socks that usually matched.

At SC Johnson R & D personnel were much better attired, even when they were working with chemicals in the lab. The women especially, it seemed, looked as if they were ready for a management cocktail party at the drop of a beaker. I think this was part of the mentality that was driving so many people in my organization to study for an MBA. So in my efforts to create a more relaxed atmosphere that encouraged people to aspire to being better scientists, and worry less about appearance, I declared that there would be one day a week when everyone could ‘dress down’. This received a mixed reception initially, but over time it became generally accepted. I learned after I left that a weekly ‘dress-down day’ was institutionalized throughout the company.

People Problems

In almost any organization the leaders will have to deal with a plethora of difficulties involving the employees. Some examples from my tenure:

One of my vice presidents came under threat from top business management because of a perception that his division wasn’t launching as many new products into the market as they felt it should. Heads would have to roll, and of course he was the target. A grown man of many talents was in tears in my office. He was the most scientifically qualified among my VP’s, and may have been encouraged by me to take a longer vision on product development. He really didn’t get his day in court. I could try to comfort him and defend him, but the knives were out, and he would soon be gone.

There were two Chinese scientists, Lee and Mark (not their real names), who were in my bailiwick, one of whom had been a graduate student of mine. They were both smart, hard working and just happened to share a lab, with rather crowded quarters. A quarrel erupted over about who owned some three inches of lab space, which was blown way out of proportion to its importance. Ridiculous as it sounds, I had to step in to arbitrate.

Incidentally, Mark had a small business of waterproofing basements on the side, and had run a private phone line into his office for that purpose! Of course that had to be removed. He got a reprimand, but we kept him because he did good science.

There were a couple of scientists I had to fire for incompetence. Not easy, since both had been with the company for many years. One appeared to be a very smart polymer chemist, and he would make impressive presentations of his work and sometimes that of others. But I began to realize that often his ‘science’ was just wrong, so that he was misleading others who worked with him. He had to go. I discussed my reasons with him, quietly in my office, after which he got up, shook my hand and thanked me! Maybe inwardly he knew he was a phony, but no one called him on it, so that this somehow put things right for him.

I had hired a scientist of excellent quality and international reputation. His wife was a scientist, so that we employed her as well. He was just a great scientist and leader. She was something else. She seemed to cause trouble wherever she went. One problem was being oversexed. The last straw was when I glanced out the window to see her and a boyfriend scientist coming to work together about an hour late. They made no attempt at being discrete about their liaison (or about getting to work on time). Because her science was good, I found a lab for her at the local university, – but not without tears in my office.

Another former grad student of mine had joined SCJohnson’s corporate research and was doing an excellent job. I asked him to work on an idea of mine (not usual, but he was willing, seeing a way to make it work). After a couple of years he succeeded and showed his results to the commercial scientists in the polymer division. They chose not to pursue the easy development of products from his technology. It could have made a huge impact in that field. My scientist was Chinese (another one), and imbued with that great Confucian tradition of respect for parents, elders, and in this case, former professors. He came to me to announce his resignation, but after entering my office it took a good five minutes before he could control his emotions to the point of speaking. Poor fellow, he struggled so hard not to cry, choke up, and be unable to speak. He finally got it out, and I of course understood. But he was a major loss to the company, all because of petty jealousies.

One Hundredth Anniversary of the Company (1886 – 1986)

The R&D organization was given a modest budget to be used in celebrating the centenary of the company. First off we decided to publish a history of the corporation’s research and development over the past century, along with some observations as to what the future could bring were we to commit appropriately to the next generation. Sam Johnson, our Chairman, had a particular responsibility to ensure that his children and their cousins would be put in charge of a strong and growing enterprise.

I asked Eugene Kitske, former head of R & D to come out of retirement to take on the project. He in turn recruited members of the staff to write chapters in the areas of their expertise and experience. I wrote the final chapter on “The Ideal R & D Organization”. The result was a handsome book of 272 pages, liberally illustrated with photographs taken from the archives, and an excellent written history of the company’s activities and growth in our domain.

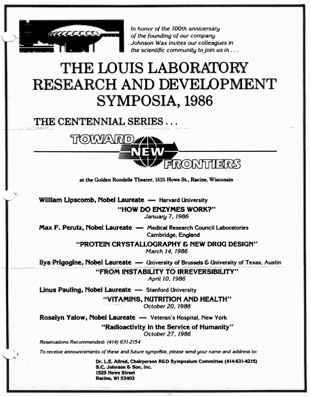

Also to celebrate our centennial I felt that we should have a series of seminars by external scientists who were highly regarded in their respective fields. So I turned to one or our best scientists, and asked him to organize it, and gave him a budget. And then jokingly I added that all the speakers should be Nobel Laureates. Well, he was a serious sort of fellow, and took me seriously. Whereupon in due course he had recruited not one, not two, but six laureates to present R & D seminars during the course of the year, one of whom, Sir George Porter, would lecture at our facility in England, and another who was none other than Linus Pauling, in my mind the greatest of them all. The lectures were of general interest, so that the public was invited. The talks were held in the Golden Rondelle Theater that had once been the Johnson Wax pavilion at the New York World’s Fair. I believe that the series conveyed a strong message that R & D at SC Johnson was world-class.

The heads of the various product divisions, mostly vice presidents, considered that their successes largely depended on their own marketing prowess. Each had his or her own R&D division, so that the scientists actually reported directly to them, and only indirectly to me. There were two corporate divisions that I was solely in charge of: Corporate Research and Corporate Engineering. I felt strongly that Corporate Research was essential to the development of new technologies that would not be focused on product lines so much as on future technologies that could serve the company as a whole.

The marketing folks were focused on short-term profits, whereas I believed that we needed someone to protect the future health of the company. After all this was the strength of a privately held corporation, and often enunciated by the Chairman, Sam Johnson. Nevertheless, jealousies arose and parts of my “empire” began to be parceled off to other divisions, including my greatest pride, the polymer research group.

Incidentally, a couple of years after I left SC Johnson, I learned that BASF had bought the entire polymers operation, and set up shop in a new facility in Michigan! I guess they couldn’t live without our technologies. Surprising that Johnson would let it go, because it was quite the most profitable division of the company.

At some point Sam came to the conclusion that we had a weak corporate research component. So he established a new and totally independent one under the direction of his youngest son and scion, Fisk Johnson (who is now CEO). The new group was staffed by some of my best scientists without any consultation with me. I tried to be supportive, but it was difficult at best. There was a lot of hubris in this new elite enterprise: they were clearly meant to be the future of the company. But at least while I was there they didn’t accomplish much.

After I had been at SC Johnson for seven years it was time for me to leave, only a year before mandatory retirement at 65 years of age. They gave me a fine golden parachute, and we parted on good terms.

And so I entered my second retirement, in some ways the best years of my life.