Chapter XII: Philadelphia

I care not whether a man is good or evil; all that I care is whether he is a wise man or a fool. Go! Put off holiness, and put on intellect.

- William Blake

1954 - 1962

Philadelphia

In Ann Arbor I had interviewed several companies for a possible position as a chemist. I wanted very much to return to Lala Land, aka Southern California, but there were no suitable jobs out there at that time. I was invited to the Texaco Research Labs at Beacon, New York and to DuPont in Wilmington, Delaware for interviews. The work at Texaco was unappealing, dealing with the rather primitive aspects of the chemistry of crude oil. On the other hand, the world of DuPont involved fabulous facilities and challenging chemical problems, and a management cadre that was technically trained and oriented. Furthermore, when during my interview in Wilmington, Delaware they took me out to lunch at their country club, there gathered to welcome me were an even dozen of former friends and colleagues from the University of Michigan. Although I am generally against following the crowd, I couldn’t refuse the generous offer DuPont made me, even though it was to be at the Marshall Laboratory of the Fabrics and Finishes Division in Philadelphia, rather than at the Experimental Station in Wilmington. On the other hand, I preferred living in the real world of a big city to that of a company town where political correctness was always a consideration.

E.I. DuPont de Nemours

My First Lab Assignment

How does this relate to house paint? Well, by co-polymerization of VAc with another, softer monomer, the particles are capable of spontaneously fusing together to form a continuous plastic film when the water evaporates from a thin film of the resulting latex. If one mixes in a dispersion of pigment particles with the latex, one gets a pigmented film – paint! It’s almost like magic.

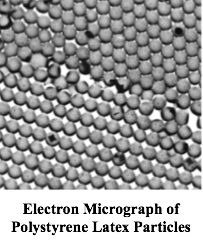

I found out in rather short order that the existing theory for how these particles are formed must be wrong. That theory was developed under the auspices of the War Production Board for the manufacture of synthetic rubber. The Japanese occupation of Malaysia had cut off our supplies of natural rubber. The theory grew out of pioneering studies by Harkins at the University of Chicago, and subsequently by Smith and Ewart at the U.S. Rubber Company. Their elegant theory was the result of experimental work and creative genius, and certainly applied well for the formation of styrene/butadiene rubber (SBR) latexes. But it was clear from my experiments that the mechanism for particle formation for vinyl acetate just had to be different.

A New Home

Incidentally, Mac asked if I had a place to stay; there was an opening in the suburban house that he shared with two other Marshall Lab bachelors, one of whom had left. Did I want to move in with them? It was almost identical to my situation in Ann Arbor, so that I readily accepted. It was a nice house on a tiny lot, well built and thus with minimal maintenance required. The neighbors were a local pharmacist, his wife and three attractive daughters. One summer eve there wafted through my open window the gorgeous sound of flute music from their house. I was entranced, and went outside to sit on the stoop and listen. It turned out that both older girls, Moira and Marcia, played the flute. They came from a distinguished musical family, with uncles who were principal oboists with the Philadelphia and Boston Symphony Orchestras. The third daughter, Henrietta, was quite a bit younger. We became good friends with M & M over many subsequent years. Moira eventually married and went to Israel with her dentist husband.

One fine day we invited Marcia and a colleague at DuPont, Murray, over for a picnic. Murray agreed to pick up Marcia on his way. They had not previously met, but by the time they arrived chez nous, it was like they were old buddies – chattering away and laughing. They even already had a couple of private jokes. Talk about chemistry! They married soon thereafter, had two girls and have lived happily ever after.

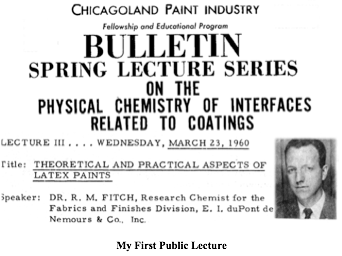

Giving Lectures

Incidentally, in preparing this picture I went to the original brochure that featured all six of the lecturers in this series. Much to my amazement, some 47 years later, I discovered that a close friend of mine here in Taos, New Mexico was one of the other speakers. We had met and had become friends, so that we knew that we were both chemists and that we had lived in Philadelphia, and that there was a chance that our paths might have crossed. But it was quite remarkable to see the two of us facing each other on opposite pages of the same brochure!

The Progress of Science is not always Smooth

My interest in the mechanism of particle formation in emulsion polymerization continued upon leaving DuPont, and throughout my academic career. The theory established in 1948 by Smith and Ewart was well ensconced around the world. It is often extremely difficult to get people to accept alternative theories to those that have been established. A most famous example is that of Wilhelm Ostwald, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry in 1909, who in 1926 when confronted with the brilliant experiments of Jean Baptist Perrin measuring the size of molecules, refused to believe in their existence. This even though Democritus had postulated the existence of atoms in the fourth century B.C! In our own time, a Japanese colleague, Prof. Norio Ise, has spent a good part of his career trying to get scientists to believe that the deeply entrenched and elegant theory of the stability of colloids propounded by Verwey and Overbeek of the Netherlands and simultaneously by Derjaguin and Landau of the Soviet Union – the DLVO theory -- is incomplete. Only lately has he been able to convince a majority of colloid scientists that DLVO cannot apply to certain systems.

Ultimately, especially after the exhaustive studies of my graduate student Chung-Hsiung Tsai, and a large endeavor by Finn Knut Hansen under the direction of my good colleague John Ugelstad at the Norwegian Technical University in Trondheim, our work was given the name of HUFT theory (Hansen-Ugelstad-Fitch-Tsai), and has been almost universally accepted.

Meanwhile, back at the Marshall Lab, a fellow by the name of Liborio Francesco Bielli was assigned to be my laboratory assistant. Everyone called him Bud. He was the son of an Italian tailor, but he had decided to follow the chemical path. Bud was very experienced, intelligent, independent, and interested in the work. We immediately hit it off. In short time he announced that I was the best experimentalist he had ever known. How could I argue with that judgment?! He always carried a two-inch roll of bills in his pocket, so that if I ever needed a loan, Bud would just peel off whatever amount I needed, no questions asked. I learned later that there was a reason for that stash of money. Every day at a certain hour Bud would disappear for a while. He was entitled to a coffee break, but his Kaffee Klatsch was different. He was in charge of the numbers games for the lab, and he went around taking bets and making pay-offs. I learned some time after I had left DuPont that Bud had been picked up by the police for illegal numbers rackets. What a sad thing to happen to such a wonderful guy! Today I suppose the only ones who would care about such betting would be any underworld competitors.

Life with Seymore

[* Note: This was simply the transformation of the water solution of the monomer, acrylamide, into a gel of aqueous polyacrylamide formed by shining ultraviolet light on the solution in the presence of a chemical ‘initiator’. Acrylamide molecules, when appropriately initiated, can link up with each other to form long, thread-like chains, i.e. polymer.]

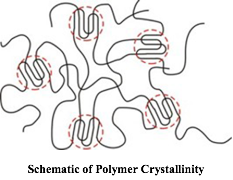

In another instance I was working with polymers that would exhibit crystallinity, which occurs when the long molecular chains form organized regions within an otherwise spaghetti-like random state, as shown in the figure here. (Polymers generally undergo only partial crystallization because of the entanglement of the extremely long thread-like molecules. They are not like salt or sugar, which readily crystallize to form hard and frangible material.) I had selected vinylidene chloride as the monomer of choice, along with an acrylic comonomer to achieve some flexibility. When an aqueous latex, comprised of gazillions of polymer particles, each particle containing thousands of these thread-like polymer molecules, suspended in water, is spread onto a surface, the water evaporates, and the particles fuse together to form a continuous film. This is the secret to latex paints. But they can only do this if the chains can move freely, i.e. they are amorphous.

My Hero with Feet of Clay

Ultimately, however, I discovered that Seymore had a somewhat compromised ethical integrity that was manifested in his “borrowing” ideas from others and entering them into undated blank pages in his lab notebook reserved for such occasions. Since the ownership of inventions is everything in industrial R & D, it is imperative that every page in a notebook is signed, dated and witnessed, and that any blank areas are crossed out so that just this sort of thing cannot happen, and that the date of an invention can stand up incontrovertibly in court. Alas, it hurt to find my mentor not only with feet of clay, but also with the feet in deep doo. It was too much, and after some three years with him, I requested and received a transfer out.

On My Own

Bubble Science

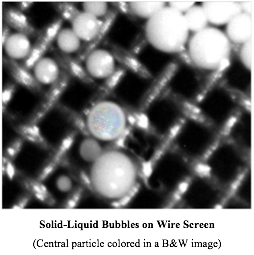

No longer under a mentor, I was now progressing up the scientific ladder, and was given more responsibility. The manufacturing plant had launched a new, latex-based wire enamel, but quickly ran into a major production problem: they always had to filter synthetic latexes to remove small particles of so-called coagulum (somewhat like cottage cheese). But in this case, the filters were immediately clogged, even though very little “coagulum” was involved. I took a sample, filtered it through a wire-mesh screen, washed what was retained and put it under the microscope.

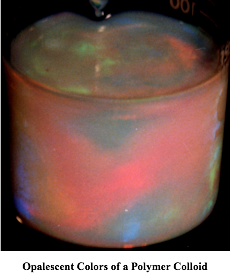

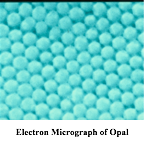

[Note: the opalescence arises from the fact that all the latex particles are very uniform in size, all carry the same electrical charge, and therefore all repel each other equally. This gives rise to a uniform array of particles in the liquid state – a liquid crystal – that exhibits Bragg diffraction. When the spacing of the array is on the order of the wavelength of visible light, beautiful colors, which change with the angle of observation, are seen, i.e. opalescence!]

Voila! Beautiful opalescent spheres of the latex* itself were somehow encapsulated in a skin that turned out to have the same composition as the polymer comprising the latex particles. How could this possibly have happened? I called these things ‘solid/liquid bubbles’. They are liquid latex on the outside with the same liquid on the inside and with a solid membrane. Soap bubbles have gas (air) on the outside, the same gas on the inside and with a liquid membrane. When you stop to think about it, it’s miraculous that simply by agitating air into a soap solution, these perfect spheres containing air are produced! Could the mechanism for forming solid/liquid bubbles be analogous? Yes, indeedy! I was able to prove this by synthesis: I took a solution of the polymer and stirred it rapidly into a surfactant solution, and sure enough, got my bubbles. The solution to the manufacturing difficulties then became clear; I suggested some changes and the problem went away.

And then serendipity arrived on the scene. The technology of micro-encapsulation was in its infancy at that time with some applications, such as in paper that produced an image upon the application of pressure. A coating could be made of solid bubbles containing an ink. The paper was almost colorless until pressure was applied by a stylus or a typewriter key whereupon micro-bubbles would burst, and the spilled ink produced a micro dot. Well, since I could make such bubbles with ease, the possibility of using my process to produce all kinds of microcapsules arose. So I started reading up on the subject and attending meetings, but ultimately I think my manager thought I was wandering too far astray, so……..

Automotive Enamels

I was asked by management to look into novel materials that could be used as the basis for paints on cars, trucks, busses and the like. DuPont had two lines of automotive finishes, Duco and Dulux. The former, used by General Motors, was a lacquer, a polymer dissolved in solvent with pigment that formed a tough film upon evaporating off the solvent in a drying oven. Dulux was an enamel, used by Ford and Chrysler, that had much less solvent, was initially liquid upon solvent evaporation, but which cured to a hard, tough film during the oven-baking process. Initially I worked on lacquer polymers, and came up with a “methacrylated alkyd”, a hybrid of two different materials that passed the stringent tests required for hardness, adhesion, shock-resistance, gloss, resistance to bird droppings, and accelerated weathering. We took out a patent and even painted a car, a colleague’s Porsche with what I modestly called ‘Fitchite’ paint. Alas, in spite of repeated attempts, we were never able to scale up the process within the time constraints imposed by corporate R & D.

Subsequently I was given the task of developing an entirely new Dulux enamel system. This was a huge responsibility, and I decided to start from scratch. Among all the myriad possibilities, I chose organosols, dispersions of polymer particles in organic solvents rather than in water. The basic technology was well known as applied to products made from PVC (polyvinyl chloride), such as ‘rubber’ dolls, textured wall coverings, floor tiles, and house siding. PVC is partially crystalline – just like my vinylidene chloride polymers – which meant that it could form perfectly stable colloids in appropriate solvents. The genius of this system was that, upon heating, the PVC dissolves forming a uniform solution. This upon cooling recrystallizes to a uniform, tough solid, no longer a dispersion, but a single piece or a film. Although PVC itself might have served as an automotive finish, its tendency to turn yellow under intense sunlight was worrisome. I needed to find a crystallizable acrylic polymer. Acrylics are noted for their resistance to ultraviolet radiation, e.g. from the sun.

A Japanese professor, Junji Furukawa at Kyoto University, had recently published the synthesis of just such a material; so I set out to reproduce the work. First, I had to make an organometallic catalyst that happened to catch fire when exposed to air. This required specialized techniques and apparatus, all of which I mastered, and in due time I had a small amount of polymer. Unfortunately for my vision and the prospects of this development, I left DuPont at this time for the Groves of Academe. More on that in a subsequent chapter. However I learned about two years later that the Marshal Lab had put some six scientists onto a big program on organosols for automotive finishes. My vision had been confirmed!

Incidentally, often upon walking to and from the lab in Philadelphia, I felt assaulted by all the trash in the streets and gutters and the bad smells in the air. We were of course in an industrial area; nevertheless it was disgusting. A note to myself went like this:

Why do men insist on working in squalor? They blame it on Industry. Few would deny that Industry would die the moment the human element left it. Refuse, smog, soot, filth and stenches are the fecal matter of Industry. It sits in the midst of it like a mad child. Men, in their avaricious scramble for money, have evidently lost sight of the pleasantries of life.

A Trip to the Orient

My Dad and Mom had moved from Mainland China to Taiwan in 1949 along with so many Chinese escaping the onslaught of Mao Zedong’s Red Army. In early 1961 Dad, now in his seventies, had suffered a stroke and had been in a coma for well over a month. Although he was getting excellent care in the Seventh Day Adventist Hospital in Taipei, the prognosis wasn’t good. I had had some success in the stock market: Beckman Instruments had increased five fold, so that Reta and I decided to cash in and go pay our last respects to my father. While there we could visit Hong Kong and Japan, where sister Edith was living in Tokyo. By the time we arrived in Taipei Dad was conscious but otherwise relatively non compos mentis. As it later turned out, Dad recovered fully, and went on heartily to the ripe old age of 96. He claimed that his miraculous recovery could be ascribed to his determination to get out of that hospital to escape their vegetarian food!

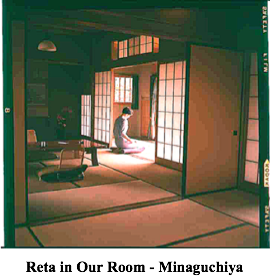

My sister Edith was living in Tokyo at the time, so that of course we had to visit her as well. In Japan we stayed in ryokans, the traditional country inns, with lovely gardens and personalized service. One destination ryokan was the Minaguchi Ya in Okitsu, made famous by Oliver Statler in his book, Japanese Inn. Statler unequivocally stated that it was “the most Japanese place I’ve been.” The same family had owned it for over 200 years, with gardens of the same age. One could walk through the back garden gate, turn around, and view Mt. Fujiyama framed in the gate, and then one was standing on the edge of the broad, sandy beach opening onto Japan’s Inland Sea. Service and food at the inn were perfect: magically the entire staff lined up to welcome us as we arrived at the front entrance, and again to bid adieu when we departed. We had a huge suite of rooms opening onto the garden. Meals were taken as we sat on the soft tatami mats on the floor. Maids shuffled in and out, bringing new dishes and drinks, and taking empties away. The senior maid stayed with us during the entire meal, to pour sake, arrange the next course, and answer questions about the food. God! I loved that place. Most sadly, a few years later a superhighway was built along the shore, separating the garden from the beach with four lanes of roaring traffic.

Oriental Art

During the trip to the Orient I had bought several works of art, a couple of finger paintings, brush paintings: one signed by ‘Sesshu’ and another exquisite ink painting of an old philosopher. So when we returned to the US we made contact through a mutual friend with the curator of Oriental art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, that magnificent institution sitting on a hill overlooking the city. She was kind enough to spend some time going over our ‘treasures.’ Sesshu was one of Japan’s greatest artists, living in the 15th century. I loved his abstract style of what came to be known as the Kano School. Sister Edith had taken me to an elegant little art shop in Tokyo where I had asked if they had any works by Sesshu; they did, and I bought. Our Philadelphia curator friend said that that was the equivalent of walking into a shop in Amsterdam and asking if they had any Rembrandts for sale. Oh! Anyway, it’s a beautiful and ancient painting of the immortal Hotei, and I love it.

When I showed the curator the painting of the old philosopher, for which I had paid almost nothing in Kyoto, she said it was either a masterpiece (my heart fluttered) or a print. No way could such delicate ink washes be accomplished by printing! She called up the museum’s print curator, who looked at it with his loupe, and then pronounced it ...... breathless waiting ......... a print. I was stunned. He said one could tell by the fact that all of the ink is on the surface of the paper, whereas in a brush painting, the ink would have soaked in. I took it to my lab, looked at it under a microscope, and confirmed that indeed all the ink was on the surface. Anyway, it’s a beautiful and ancient print of Hotei, and I love it.

Nesting

The First Addition

Our little nest was fine for the two of us, and even for a third. It became apparent that there was indeed to be another, and in due course David Hamilton Ashmore Fitch arrived. Apparently he was anxious to get going, and made his debut two weeks before he was expected. ‘David’ was a good, Judeo-Christian name; Hamilton simply sounded distinguished; Ashmore was my father’s middle name. When my Dad asked me about why we had used it, I said that it was a family name. He said, “No it’s not.” I said, “Well it is now!”

Reta turned out to be an ideal mother. She suckled the young one, as we both agreed that breast-feeding was the healthiest way to go. When little David was finished, occasionally I had the pleasant task of consuming the leftovers. Our baby health care bible was Dr. Benjamin Spock’s Baby and Childcare in which the good doctor seemed to anticipate every medical complaint and anxiety we had, and prescribed exactly what was needed. His advice on the non-medical side of child rearing was, on the other hand, almost totally wrong in our opinion.

The Second Addition

The children, and now the grandchildren, have been at the very center of Reta’s being. She has a myriad of other interests, but the kids occupy the center. Just a little more than two years passed when Douglas Gerald Fitch came onto the scene. He had been a restless one for several months prior to his birth, just kicking up a storm. One Sunday, a full month before Doug was due, we had decided to spend a pleasant August day north of Philly in the pretty riverside village of New Hope, and to have lunch at an elegant little restaurant there. When we awoke that morning, however, Reta started having contractions every five minutes, but she insisted she wasn’t going to miss this day in New Hope, and after all, it was still a month before she was due.

“Well, false labor is pretty common; don’t worry.”

“The water just broke.”

“Yes, well maybe you’d better bring her in. I’ll meet you at the University Hospital.”

We roared off, passing miles and miles of Sunday traffic, driving on the shoulder of the road, desperately trying to find a policeman who could escort us in.

Finally a Park Guard pulled us over. I jumped out exclaiming how happy I was to see him. Could he escort us? He said he’d have to put her in his truck and he could only take her to the nearest hospital. I opened the door to our car to show him Reta soaking wet and in labor. Did he really want to assist in the delivery in his truck? I insisted that since the doctor was waiting for us, we had to get to the University of Pennsylvania Hospital. The officer phoned for, and got permission to take us there. He had only a small yellow flashing light on top of his cab, and no siren. So he beeped his way through the traffic, as we followed closely. At the hospital emergency entrance I leaped out of the car, ran to the registration desk where there was a short line. I was told to wait my turn, even though I protested that my wife was in labor. But when they saw Reta accompanied by the uniformed guard, they dropped everything, and whisked her off in a wheelchair. Twenty minutes later Douglas made his eager entrance into this world. The pediatrician said he had never seen a baby with better muscle tone.

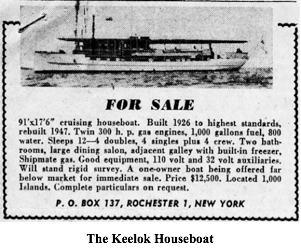

A Floating Home?

Our little apartment was now bursting at the seams. I set out to find roomier accommodations. Just at that time an ad appeared in the newspaper for a cruising houseboat, fully furnished with linens, dishes, cutlery and kitchen utensils with four staterooms and sleeping space for 12. All this for a mere $12,500. What a deal; we couldn’t buy and furnish a house for anything near that. It turned out to be a 91 foot corporate cruising houseboat, recently refurbished, with an oak hull, twin 300 hp gasoline engines and docked in Lake Erie at Buffalo. I started out looking for financing, insurance and a crew to help me bring it down the New York Barge Canal to Philadelphia. In the meantime I signed up for a course on motorboats and navigation. After several weeks of

A Home at Last

We plunged into remodeling, stripping eons of wallpaper, painting, redoing the floors, carpeting the living room etc. In the process of laying the walls bare we came across large, penciled cartoons of what looked like comic-strip characters on the living room wall! We couldn’t bring ourselves to paint over them; so we covered the wall with bamboo screens just pinned to the plaster that gave a warm ambiance to the room, along with our new gold-colored wall-to-wall carpet. The house soon became a home. A big, grassy back yard was ideal for the boys to play – in a little plastic pool or on a swing set, or they could make a mess with paints.

Extracurricula

Science Club

A colleague at the Marshall Lab, with whom I often shared rides to work, was a member of the Religious Society of Friends – or Quakers – and he was interested in the development of young people, in line with the focus of the Friends on schools and universities. [Did you know that some of the best institutions of higher learning were founded by the Quakers, e.g. Bryn Mawr, Haverford, Cornell, Johns Hopkins, and Swarthmore?] At any rate, Bill was involved with a Science Club for young kids in their early teens, and at one point he asked me to join him. It turned out to be a very rewarding experience. Attendance was entirely voluntary, so that we only had a handful of boys at any given meeting, and they were all motivated. My job was primarily to be there for them, answer questions, make suggestions, guide them in their thinking, and more or less stay out of the way. Shouldn’t all education be that way?

Amos Bronson Alcott said it well:

“The true teacher defends his pupils against his own personal influence. He inspires self-distrust. He guides their eyes from himself to the spirit that quickens him. He will have no disciple.”

One lad in particular, John Prenis, was a young genius, with a particular passion for geometry, but also a love for all things scientific, including chemistry. He was the most faithful attendee, and he always came with something he had been working on. When I left Philadelphia, I bequeathed to him and a couple of the others my chemicals and apparatus, which they divvied up among themselves. What a joy to have worked with such a creative and energetic mind. He taught me a lot!

The PSPCC

Another friend induced Reta and me to become volunteers for the Pennsylvania Society to Protect Children from Cruelty (currently the Philadelphia Society for Services to Children). This organization was founded in 1877 as a spin-off from the Society for the Protection of Animals from Cruelty! I guess that prior to that time animals were more important than children. This group had a shelter/home for children who were separated from their parents by order of a court because of extreme abuse. Our job was to act as surrogate parents for a few hours one evening a week. The first thing that struck me about those kids was how bright, happy and active they were. They had none of the dullness in their eyes or actions characteristic of neglected children. Clearly we had to distinguish between physical abuse and neglectful abuse. We didn’t ask them how they were abused, but sometimes it came out. One girl told us that she was punished by having her hand held in the flame of their stove. Another, when I was clowning around with them one time, said that I acted like his father when he was drunk. It could be really heart wrenching at times. But the children were an absolute delight. They evidently had been rescued before permanent damage had been done, much to the credit of the PSPCC. This all occurred prior to our having children of our own. We had to give it up when David was born.

Zion’s League

Reta had found a compatible group of Reorganized Latter Day Saints (the church she had grown up in) in the Philadelphia area, and encouraged me to participate in their activities. I soon found myself teaching Sunday school, or “Zion’s League” as they called it, with a pretty decent bunch of kids. I continued to be a conflicted Christian, but thought that this work was worthwhile. Conflicted, as you might expect of a scientist who was brought up in a deeply religious and disciplined family. But these were internal contradictions, and didn’t interfere with my ability to work with these kids. Reta of course worked with me, pretty much free of such concerns.

Hobbies

And I could pursue a hobby of gardening and cultivating bonsai, which soon grew to a passion. I took art lessons from Howard Weinstone at the local synagogue, making my own paints from alkyd resins and pigment dispersions purloined from the lab. I even managed to sell some of my art!

But it led ultimately to a long and happy friendship with Carlton and his family. Some time later he asked if I would be willing to show some of my mini-trees at the Japanese teahouse in Fairmount Park where the Horticultural Society was going to hold an exhibition of bonsai. I was honored and delighted and did!

Hobbies were getting to be too much, which led me to cut back sharply. I gave up painting and kept to bonsai and a minimum of gardening.

Heading for the Groves of Academe

Some of the reasons why I finally left DuPont are taken from personal notes written at this time:

June 14, 1962

Depressed situation at work; unsatisfactory. Everyone ashamed of what he’s doing because, though trained in use of the Scientific Method, we spend our days using crass and empirical approaches to solving problems on hopelessly complex and ill-defined systems. No time is ever spent on the proper definition of a system. Management constantly interferes with our work, and experiments are constantly ‘suggested’. My future position has been threatened as a result of “uncooperative” attitude when I try to follow my own research ideas to the .... de-emphasis on the ideas of management.

Nearly everyone at the Marshall Lab wants out, but is very hesitant to leave because of fringe benefits: thrift plan, bonus plan, life insurance, etc. So “we bear those ills we have than fly to others we know not of,” and sink more deeply into our own shame, despising ourselves and those for whom we work.

Alternatives? Business for myself or teaching. The former gives promise of wealth, excitement and accomplishment; latter gives promise of intellectual pursuits most gratifying to my soul (!) but little wealth. Both give promise of FREEDOM. This I crave.

Well, maybe I’d had a bad day, but the general thrust was certainly valid. A couple of DuPont colleagues and I discussed at length the idea of starting a business of manufacturing fine organic chemicals. But the more we got into it, the more we realized that we would be spending even less time than currently on ‘doing science’ and more, on business matters. My passion was pure science and if it had a practical application, so much the better. I had decided early on that ultimately I wanted to be in academia, but I felt that I needed practical experience in industry prior to that. Only a casual look at colleges and universities reveals that many professors are second or third generation in the scholastic world, and have very little connection to the real world outside of their chosen profession. This is not healthy, especially in science and technology, for the education of the future leaders and workers of our country. I did not want to make that mistake. My parents had not worked in industry or the corporate world, so that it was imperative that I had some experience there. This practical experience at DuPont would also be of great value, as it turned out that I subsequently became a consultant to a number of companies.

My first thought was to try to stay in Philly because we had come to love our unique City of Brotherly Love. I went to see Prof. Charles C Price, who was the chairman of the Department of Chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania and a polymer chemist. By this time, after taking a night course in polymer chemistry (after grad school I had promised myself never to take another course!) and working for the past eight years primarily in this discipline, I fancied myself as a polymer chemist as well. But Price said there were just no openings at Penn. There was an advertisement for such a person by the School of Chemistry at North Dakota State University in Fargo, the only opening in polymer chemistry in the United States that year that I was aware of. Price suggested I take a look at it.

So off I went on an interview trip to Fargo, and was quite pleasantly surprised at what I found.

♣