Chapter X: Ann Arbor

In seeking wisdom thou art wise; in imagining that thou hast attained it - thou art a fool.

- Lord Chesterfield

1950 – 1954

Ann Arbor

Arrival

Two scruffy-looking young men in T-shirts appeared in the TA office on my first day there, a hot September afternoon. They introduced themselves as Randy Perry and Gil Sloan, and stated that they were looking for a new recruit to share their rented house occupied by them and 3 others, all chemistry grad students. I needed a place to stay, I was used to cooking and housekeeping for myself, the rent was low; so I agreed to join them – a very good decision as it turned out.

All the chemistry neophytes had to take a placement exam in a big lecture hall one evening. While we were struggling with remembering our undergrad chemistry (which for me was last seen over 18 months ago) there came a booming baritone voice singing Gluck arias from somewhere in the corridors beyond, ♫ “Che faro senza Euridice.......” ♫ It wasn’t until later that I realized that this was Gil, my new housemate!

Killer Courses

Chemical thermodynamics at the graduate level almost destroyed me, and the next semester’s infrared spectroscopy in the Physics Department (my chosen minor) just about executed the coup de grace. Partial differential equations applied endlessly and boringly to problems of little interest in ‘thermo’, and the application of quantum wave equations to the vibrations of molecules in the infrared left me uninspired and often unable to cope. I learned one thing well from our otherwise rather dry physics professor though. It had to do with the invention of a very sensitive heat detector called the bolometer:

Professor Langley invented the bolometer,

Which was something like a thermometer.

It could measure the heat of a polar bear’s seat

At the distance of half a kilometer.

At the end of my first year in Ann Arobr I received a notice that I was no longer eligible to continue in the Rackham School of Graduate Studies of the University of Michigan – a thunderous blow that I had not anticipated at all. I had passed these courses, but at a level below the overall minimum standard. Those hours of poker at Dartmouth and on the beach in La Jolla were having their effect. I was out. In desperation I made an appointment with the Dean of the Grad School, a kindly gentleman, who seemed to sympathize with my plight. I begged for an extension on my probationary time, which he granted. The next two semesters I was careful to choose courses which were likely to be easier for me, and earned all A’s. I was in!

I had now qualified for the Master’s degree. So I paid the $25 fee, and in due course received an elegant document to that effect. But I was pursuing the Ph.D., a research degree. It meant that I had to pass two foreign language exams and a series of Preliminary Exams besides writing a thesis on original research. A colleague, Harry Blanchard, and I closeted ourselves in an empty classroom every day for weeks to review and re-learn our physical chemistry. It worked. We passed. Today the universal language of science is English, but back in the ‘50s to be a scholar in science meant that one had to be able to read the non-English literature in the original languages – almost exclusively European. There were no translations. I chose French and German, translating several pages from scientific papers chosen by the examiner, but being allowed to use a dictionary. These I passed as well. It was tougher in earlier times, when every scholar in ‘natural philosophy’ at the University of Michigan had to be passably fluent in both Greek and Latin!

Research

Henceforth it would be full time research. A doctoral candidate ordinarily starts out by interviewing professors who are involved in research in the field of the student’s interest, and then by mutual consent, they team up. The prof lays out a plan of work that is supposed to take about 3 to 4 years to complete. I went to work for Prof. Joseph Halford, a physical-organic chemist, who was primarily a theoretician in the field of the internal motions of atoms in molecules, and their electronic structure. These things tend to be very fundamental science, rather esoteric, and with no practical applications. It was pure chemistry and purely for the development of new knowledge. My assigned topic was “An Investigation of the Degree of Aromaticity in conjugated Seven-Membered Nitrogen Heterocycles.” These are molecules with seven atoms in the shape of a ring, and whose electrons get smeared out over the entire molecule under certain conditions. The name has nothing to do with their smell. My job was to determine whether such molecules fit the behavior predicted in 1938 by the German theoretician E. Hückel.

This was total immersion, which would at times put my mind into realms beyond the ordinary. Earlier, in a class given by Wyman Vaughn, we were given a take-home exam with the invitation to call him if we had questions. During my work on the exam I needed to ask a question, called Wyman, and he explained the situation so that I could understand. I thanked him, whereupon he said, “Bob, do you know what time it is?” “Uh, no; what time is it?” “It’s 2:00 o’clock in the morning.” I just had no idea, and apologized profusely. Wyman was kindly and forgiving, and still managed to find it in his soul to give me a decent grade.

On another occasion, after many long hours in the lab, with my head full of chemistry, I went home in the early hours with a lovely, gentle snow falling, turning the tree-lined streets into a magical fairyland. A road crew was out shoveling the most beautiful, large, cubic shaped crystals onto the street. This just added to the enchantment of the night. I asked one of the men, “Is that sodium chloride or calcium chloride?” He stopped, leaned on his shovel, looked at me a bit strangely and replied, “That’s salt.” Me: “Oh.” My mind was snapped back to the real world! The lesson stayed with me that when two people from different worlds meet, they have to find a common language before meaningful communication can take place, even when they both speak English!

Extracurricular Activities

Ann Arbor offered much more than lectures, seminars, courses, exams and long, lonely hours in the lab. Gil’s great baritone voice belted out operatic arias while he was cooking supper at home or cooking up novel chemicals in his lab. He had a collection of classical records. One day he was playing a symphony that I hadn’t heard before, and which moved me greatly. When I asked him what it was, he said “Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony”. I had just never heard anything like that before, and my life-long love of classical music started at that moment.

For some distraction from chemistry I joined the U of M Choral Union, after passing the tryouts. It was a group of some 350 voices. Every Christmas season we sang Handel’s Messiah, and every spring we hosted the Philadelphia Orchestra in our May Festival, a weeklong affair during which we sang a major chorale (Bach’s Mass in B-minor, Mendelssohn’s Elijah) on one night and other relatively minor pieces in a second concert. During the rest of the week we could sit in our bleachers behind the orchestra on stage in Hill Auditorium, watching Eugene Ormandy conduct with his eyebrows and hands. It was a thrilling experience. It also gave an insight into the human side of such illustrious music-makers: on one first night as the tympanists set up right below where I was sitting, one opened his music folder to show a lovely nude on the inside cover!

Back at our home-away-from-home we occasionally had a culinary experience. Gil and I loved to cook creatively, whereas Randy was strictly a meat and potatoes man. Gil decided one time to make sauerbraten, a beef dish cooked in vinegar and herbs. He obtained an inexpensive cut of plank steak and sprinkled it liberally with meat tenderizer. The steak was marinated with the vinegar and herbs for a couple of days, and then subjected to pressure-cooking to ensure its tenderness. On opening the pot, Gil exclaimed, “Oh my God!” as he peered at the contents. The steak was indeed tenderized; it had been reduced to a brown mush, greatly resembling what would have been its final outcome after digestion. We just couldn’t eat it.

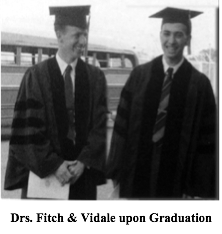

After a couple of years Randy finished his degree work and left us. We recruited Guido Vidale, another grad student working in the field of physical chemistry, to share our apartment. Guido was born and raised in Italy, was very bright, friendly and a minor master of traditional Italian cuisine learned from his Mama. Upon arrival he had in one hand a single suitcase, and in the other, bunches of fresh herbs. Ah, such flavors he could conjure up in our kitchen, and what exquisite ways he had of cooking vegetables with a minimum of water and a maximum of flavor!

Apparently I was something of a party animal, no doubt because of my Dartmouth upbringing. At any rate, on occasion when the grind was overwhelming, and it was clear that some steam needed to be released (bad mixed metaphor!), I would make the rounds of the graduate students in their labs announcing that there would be a gathering of the clan at one of the local taverns, and everybody would show up. After a couple of hours of beer-laced boisterous conviviality everyone had re-connected, solved the world’s problems and had a great good time. We could all go back to work renewed.

Prof. Bachman and RDX

The U of M had several renowned professors, one of whom was Werner Bachman, whose lab – empty at the time - I had taken over. During World War II he was asked to lead a team to develop a manufacturing method for the production of RDX, a plastic explosive invented by the British. A basement laboratory was cleared for action, Bachman moved a cot in so that he could devote 24 hours a day when necessary, and went to work with a team of students. The research was dangerous of course, but they never had an explosion. They did however have an occasional ‘fume-off’ in which the entire contents of a large flask were transformed into vapor in a matter of seconds! Of course they worked in fume hoods, so that the vapors all went out the stack. In time they had their process, they designed a manufacturing plant, and oversaw its construction and production. RDX, used in depth charges, torpedoes and other armaments, was greatly instrumental in turning away the German U-boat menace and clearing the way for ultimate Allied victory. Bachman went home and collapsed from ill health for months. While I was there, he apparently felt strong enough to give a lecture to the chemistry department on his war efforts. He didn’t look very good during the lecture. He died the next day. Clearly, he gave his life to his country.

Teaching

Learning chemistry requires laboratory experience, a greatly added burden on the instructional infrastructure that many other departments don’t have. This means a cohort of teaching assistants is needed in addition to laboratories and supplies, an expensive proposition for any institution of higher learning. The flip side of that is that it provides financial assistance to many graduate students. We “TA’s” had to conduct recitation sections in which we reviewed the lectures and worked on assigned homework problems, as well as preparing for labs. The latter were my opportunity to work directly, one-on-one, with individual students. I seemed to come naturally to the Socratic method: a laboratory session would go something like this:

Me: Whatcha doing?

Student: I’m adding 5 milliliters of this solution to my flask.

M: Why are you doing that?

S: The lab book says to do it.

M: Why do you suppose the lab book says that’s the next step?

S: (Leafing through the lab book) Uh, I don’t know.

M: Do you think there is any connection with last week’s lecture by Prof. Blank?

S: (Leafing hopelessly through his chemistry textbook and lecture notes, looking at the clock, and getting a little annoyed) Is there supposed to be?.............and so on.........

Well, to be sure that is a worst-case scenario, but not unusual. Often I could lead the student to the right answer, which he had within him, but had not made the connection. It was always satisfying to both the student and to me when enlightenment came. Good Old Socrates!

In a particular experiment in organic chemistry lab the students had to distill benzene from a reaction mixture, and they were cautioned that because of its flammability and volatility, they should not use a Bunsen burner, but rather hot steam available at their benches. Well I found one girl starting her distillation with a burner. So I quietly got a big CO2 fire extinguisher, and stood behind her waiting for the inevitable. She didn’t notice me until her apparatus caught fire. She jumped back in alarm, and then there was a loud whoosh as I let go with the extinguisher, putting out the fire and frightening the poor girl even further. She read her lab instructions more carefully thereafter.

On another occasion, in an advanced lab, a foreign student asked me for help. He wasn’t getting the product his instructions indicated he should have. I looked over the instructions and then noticed that his reaction mixture, being stirred in a flask, looked quite extraordinary. There was some strange-looking solid material when only liquids should have been present. I asked him what the solid was. “That’s acetyl chloride.” I pointed out that acetyl chloride was a liquid. “No, no, it’s a solid,” he insisted. I asked where he got it, and he showed me a new metal canister, labeled correctly. He lifted the lid and showed me the solid, sure enough. I asked him to remove more of the solid, whereupon he discovered a bottle of the liquid acetyl chloride inside. The solid was simply vermiculite packing material! It’s interesting how people can be so positive about things in the face of expertise immediately available. At the same time, as T.H. Huxley said, “No progress is made without the absolute rejection of authority.” Nevertheless, some allowance should be made, as Kipling said in his famous poem IF: “If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you, And make allowance for their doubting, too.....”

There were often pretty girls in the labs, and it was always tempting to date them. But I felt that it would be unethical to do so; when it came time to give out grades, there could be a conflict of interest. I did date some of my former students, one or two of whom became quite close friends. [See the chapter on Falling in Love.]

Summers

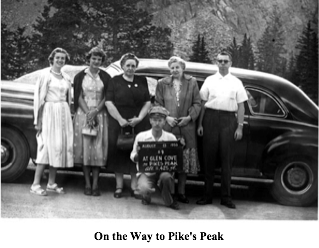

Summers were spent in research without the distractions of teaching. During my penultimate year, though, the opportunity arose for a summer internship at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in the mountains of New Mexico. I applied, was accepted, but then had to obtain a “Q-clearance” from the FBI prior to arrival. In due course the spooks came to the University and asked my friends if I was loyal to the United States, and did I have any connections to that fearful Communist Party? But summer was almost upon us, and still no security clearance for me. They must have decided that my Chinese origins needed looking into. So when the semester ended, I decided to go somewhere close to Los Alamos to await word from the FBI. I chose to do some camping in the mountains above Colorado Springs, modified my 1937 Chrysler Coupe so that I could sleep in it, and headed for the hills. A periodic check with the Chemistry Department secretaries provided no news from Los Alamos. After a couple of weeks I was out of money, so that I came into town, rented a room in a private home, and then found work, firstly waiting on tables and later driving a tourist limousine up Pike’s Peak for the Antlers Hotel. Going up the gravel road to the summit at over 14,000 feet was an exciting experience, with sheer drops off the edge of the road of over a thousand feet in some places. I’d tell my lady passengers that if they were frightened, to do what I did: just close their eyes. This always elicited screams of delighted fear. After a few trips, I realized I wasn’t getting any tips. So I went to a sign-maker and asked him to make a couple of cards that read:

I tucked a card under the limo’s sun visor, held there by a rubber band, along with a little envelope that had to be delivered at an intermediate stop on each trip (I think the latter was to ensure that I was doing what I was paid to do.) I excused myself, flipped the sun visor down, took out the envelope and left the passengers staring at my little sign while I went into the station to deliver the document. It worked wonderfully! It was a relatively gentle reminder, and I didn’t see how the hotel could object if they discovered it.

Colorado Springs provided a summer idyll, with perfect weather, no real pressures or responsibilities and lots of spare time. I met a fellow who loved barbershop quartet singing, and who got me to attend a few meetings of the SPEBSQSA, the Society for the Preservation and Encouragement of Barber Shop Quartet Singing in America. Like the members, “I love to sing those minor chords and good, close harmony.” (Taken from their theme song.) I went to Colorado College for an occasional cultural event, such as Sunday afternoon concerts, made friends with the locals, and had a few dates with my tourists after dark.

The summer was winding down, there was still no word from Los Alamos, and I wanted to see Phyllis in California. My brother Albert was in Salt Lake City in some kind of Texaco training program; I could see him en route. So I hopped into my trusty ’37 Chrysler Coupe and headed west. Albert was supposed to be staying at the grand Hotel Utah, but they had only a cancellation of his reservation on record. The local Texaco office said that he was staying at a much more modest place where indeed I found him, much to his surprise, as I had not warned him of my coming. He took me out to a nightclub that evening, something I had almost never done on my own, and introduced me to two Mormon young ladies, who appeared to take the church’s prohibitions on drinking with light regard. They were not prostitutes; they were free – in more ways than one. I ended up in bed with the blonde the first night, and the redhead – Ruby – the next. Ruby was quiet, warm, sweet, and affectionate. I kinda fell for her. She disappeared in the morning; I went looking for her, but she was gone.

How I missed her, how I missed her,

How I missed my Clementine.

So I kissed her little sister

And forgot my Clementine.

It was no doubt just as well for me. I bade farewell to brother Al, and went looking for Phyllis instead. Alas, it turned out not to be a good thing. Phyllis was at home in Beverly Hills, having married her soybean futures man, and having divorced him, all in the three years since we had parted. And she had acquired a serious addiction to alcohol. At the posh restaurant where we had lunch, she surreptitiously poured herself vodka into her water glass from a plastic bottle in her purse. Her hands shook. She wasn’t much fun, and I didn’t know what to do except to bid her a rather early farewell. She wrote me a sad “mea culpa, mea maxima culpa” letter some time later. It was our last communication.

I drove back to Ann Arbor, sadder and not much wiser.

The Draft

There, waiting for me, was a little document from my Draft Board in New York City, saying that because I had not responded to their previous letters, I was to report immediately for military service. What a shock. The Korean War overlapped most of the time I was in graduate school. Prof. Parry had successfully interceded on behalf of the TA’s to obtain deferments for us because the nation needed scientists. But during my summer sojourn to the Southwest (ironically, not to Los Alamos), the Chemistry Department secretaries didn’t forward my mail from my draft board. After a flurry of frantic correspondence, and appeals to higher authorities, I finally received another deferment “By order of the President” no less.

The Final Push

I plunged back into the usual graduate research student routine. My professor, Joseph Halford, took little interest, and had never visited my lab. Towards the end of summer, 1954, I decided it was time he had an update, so that we could decide where to go next. He came to my lab, and I gave him a pretty formal review of where things stood. To my amazement, at the end of the session, he said, “Well it looks like you should write it up.” I didn’t say much, but I was thinking, “WOW! You mean I’ve done enough for a Ph.D?” I started typing a rough draft on an old mechanical typewriter in the TA office, and Reta, my girlfriend, kindly consented to do the final draft, as well as to make photocopies of charts and graphs. Those were AX days (ante Xerox) when copies were made by photographing onto film, developing the film, projecting the image onto enlarging paper, and developing that – all wet chemistry.

I had achieved some kind of record in getting through in just three and a half years. Graduate students often spent 4, 5 or even 6 years getting a degree. Now I had to go out and once again face the real world.

♣